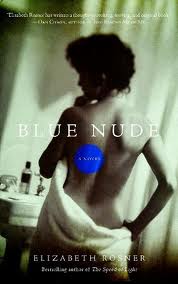

Born in the shadow of post-war Germany, Danzig is a once prominent painter who now teaches at an art institute in San Francisco. But while Danzig shares wisdom and technique with students, his own canvasses remain empty, for reasons he doesn’t understand. One day, he and his class begin sketching a new model, a young woman named Merav, the Israeli-born granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor and herself a former art student. Danzig is immediately taken with her exceptional beauty, sensing that she may be the muse he has been missing. Challenged by Danzig’s German accent, Merav must decide how to overcome her fears. Before they can create anything new together, both artist and model are forced to examine the history that they carry.

Blue Nude recounts the events that bring Danzig and Merav together, including their disparate upbringings, their respective creative awakenings, and their similarly painful, often catastrophic, love lives. Using words to paint the landscapes of body and soul, Rosner conveys the art of survival, the complexity of history, the form of exile, the shape of desire, and the color of intimacy. Blue Nude is the narrative equivalent of a masterpiece of fine art.

Critical Praise for Blue Nude:

Poet and novelist Rosner (The Speed of Light) has written an elegiac story of an emotionally and creatively starved artist and his muse. Danzig is 58, a German painter whose once promising career has stagnated into teaching life drawing classes at San Francisco’s Art Institute. Then Merav appaears, a lovely Israeli woman, also an artist, who models in his classroom. Merav struggles with instinctual distrust of Danzig: “The poses she took in the first session were all in the shape of fear: a woman turning away from something threatening; a body in flight; the curled-up shape of self-defense, protecting the heart, the belly.” When Danzig asks Merav if she will model for him privately, she’s reluctant, but their relationship evolves. The present diverges to the past, and Rosner develops her protagonists as though they are pieces of art, slowly becoming unveiled. Although their backgrounds are divergent—Danzig lived in fear of his father while Merav grew up in the safety of a kibbutz without one—their interior lives are similar. Rosner’s multilayered composition is rendered in beautiful, spare prose and will resonate long after the last page.

– Publishers Weekly

“We watch, spellbound, as the story seems to levitate midair, as the characters seamlessly unfold a plot that is no less than fascinating. Using the rhythms of poetry, Elizabeth Rosner has created a lyrical tour de force.”

– Linda Gray Sexton, author of “Half in Love: Surviving the Legacy of Suicide.”

Rosner has a painter’s eye and a poet’s ear. BLUE NUDE is a luminous book about painful histories — both private and global — and how they stay with us even as they travel through to become something else – quite possibly art. A book both heady and tangible, both unflinching and generous, but always beautiful to read.

– Karen Joy Fowler, author of NY Times Bestseller The Jane Austen Book Club.

Through German artist, Danzig, and Israeli muse, Merav, Elizabeth Rosner builds a bridge from loss to reconciliation, from anger to understanding. Blue Nude is a lyrical exploration of how we — as individuals and as a society — move past our separate histories and toward a shared redemption. This is truly a lovely book.

– Meg Waite Clayton, author of The Wednesday Sisters

“Blue Nude is a novel which spans time and continents, from post war Germany to California to Israeli kibbutzim, a novel which explores the big questions of history, fate, art, how we choose to live the lives we’re given–and yet it’s also wonderfully intimate as well in its exploration of the hearts of its individual characters. Elizabeth Rosner has written a thought provoking, moving and original book.”

– Dan Chaon,

author of You Remind Me of Me

“Rosner takes on complexity with a brilliant poet’s insistence that the body can never surrender cultural legacy. Blue Nude is easy to pick up and, in its suspense, hard to put down. Its sensitivity to detail acts as a love letter to the world.”

– Edie Meidav,

author of Crawl Space

“What I like especially about Elizabeth Rosner’s Blue Nude is its patience and careful pace, both utterly appropriate to a story of troubled reconciliation. In its insistence that sweetness (honeyed, not saccharine) can come out of violence, Blue Nude resembles the astonishing Israeli film Walk on Water which also takes on the contemporary legacy of German-Jewish relations. It helps that Ms. Rosner has a poet’s eye and an enviable ability to allow both her lapidary sentences and her deeply complex characters space to breathe.”

– Jonathan Wilson

READING GUIDE:

Introduction

Award-winning poet and bestselling author Elizabeth Rosner has written a moving story of history, legacy and ultimate reconciliation as explored through the relationship between a German artist and an Israeli-born model.

Born in the shadow of post-war Germany, Danzig is a once prominent painter who now teaches at an art institute in San Francisco. But while Danzig shares wisdom and technique with students, his own canvasses remain empty, for reasons he doesn’t entirely understand. One day, he and his class begin sketching a new model, a young woman named Merav, the Israeli-born granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor and herself a former art student. Danzig is immediately taken with her exceptional beauty, sensing that she may be the muse he has been missing. Challenged by Danzig’s German accent, Merav must decide how to overcome her fears. Before they can create anything new together, both artist and model are forced to examine the history that they carry.

Blue Nude recounts the events that bring Danzig and Merav together, including their disparate upbringings, their respective creative awakenings, and their similarly painful, often catastrophic, love lives. It explores the moral implications of their relationship and the lasting impact of the Holocaust on post-war generations in a lyrical and compelling way.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. The concept of “beauty” is discussed throughout the novel in its many different forms. How does each of the characters see beauty? Do you find your own awareness of beauty has been affected by reading the book?

2. The past continually visits Danzig and Merav, both separately as well as when they are together. Discuss how the legacy of the past impacts subsequent generations. Can they ever move beyond their history? How much more burdensome is their past, given their ancestor’s experiences with the Holocaust? Are they ever able to reconcile their pasts?

3. This book largely tells of the connection between Merav and Danzig—but where does Margot fit in? Why is she the only other character to have chapters told from her point of view, and how does this impact the book overall?

2. How does Merav’s early life in Israel (growing up on a kibbutz, serving in the army) affect her later life in the United States? Which values does she bring with her, and which does she leave behind?

4. Danzig’s sexual impulses continually conflict with his artistic inspirations. For instance, after having sex with Andrea for the first time, Danzig realizes he can no longer be artistically inspired by a woman he has been with. Why do you think this is?

5. “I never wanted to be anyone’s father.” Danzig refuses to care for his and Andrea’s baby on page 78. What do you think is holding him back from fatherhood at this point? Also, when Andrea sends him a scathing letter in the mail, is she justified in doing so? Why or why not?

6. Merav is both an artist and a model. How does she reconcile the two? Does it seem possible for her to be both at once, or must she ultimately give up one to make room for the other?

7. Describe the balance of power between Danzig and the models who pose for him. Who is really in control: the artist, or the muse? Is the balance of power different when they are in the classroom compared to in Danzig’s personal studios?

8. Danzig’s fight with Susan (pages 84-88) is a pivotal moment in this story. Does anything change in him after the fight? If so, what? How does the news of her subsequent suicide attempt affect him?

9. How did Merav’s relationship with Gabe differ from her relationship with Yossi? What did Merav get out of her marriage with Gabe, and why did she feel she had to end it?

10. Both Danzig and Herr Hoffman display skeletons in their classrooms – “Doctor Memento” and “Herr Doktor.” Why do you think Rosner chose to give them these names?

11. Merav and Danzig might be considered opposites: She is a woman, he is a man; she is Israeli, he is German; she is the model, he is the artist, etc. Their differences are overtly apparent throughout the book, yet perhaps they share more subtle—and some not-so-subtle—similarities. Consider some of these similarities.

12. Rosner often focuses on the colors her characters experience; for example, Gabe dreams in “red light” (142), Danzig finds Margot with skin “not just white but pale blue, gray-blue” (110). How do these references to color help bring the story to life, and why do you think Rosner has made this theme so prominent?

13. Merav is repeatedly told the story of her grandmother’s discovery by a “young German soldier” in a barn. Why do you think Rosner has placed Merav in this same barn for the final scene of the story? Do you think Merav realizes the significance of the barn, or do you think she is completely unaware?

14. In the final scene in which Danzig paints Merav, Danzig muses on how the image of Merav in the tub has merged “into one echo, one story” with his finding Margot in the bath so many years ago. Discuss how painting Merav may have helped Danzig to cope with his past. Consider how Merav is also changed by posing for him.

15. Do you consider this to be a love story? If yes, in what way? If no, why not?

top

READING GROUP ENHANCERS

1. Sign up for an art class with the members of your reading group. Many community centers and colleges offer a variety of beginning art classes for adults. Also, private teachers may be available in your area if your group would prefer a smaller class.

2. Both Merav and Danzig listen to music while painting/posing, and several musical artists are mentioned throughout the book. Compose a playlist of your own with the members of your reading group and try using it as background music during a group painting session. You can try painting a specific subject, such as a person or an object, or you can let the music lead your brushes.

3. Visit a Holocaust museum, or sit in on a speech given by a Holocaust survivor. While the experience may be powerful, and perhaps overwhelming at times, it may give you and the members of your reading group a new perspective on the novel.

4. Hold a free-write session in which the members of your group have a specified amount of time to write whatever they like. Try picking a certain theme in the book, such as memory or reconciliation, on which to write. When everyone is finished, you can choose to share your writings or keep them private.

5. Merav appreciates nature’s beauty as she is on a five-day hike with Yossi and Tzvi, the eccentric kibbutz artist. Go for a hike on a local trail with your reading group; after all, you don’t have to be in the deserts of Israel to appreciate what nature has to offer.

top

AUTHOR QUESTIONS

In a previous interview, you mentioned you like to do research by talking to people and listening to their stories. Do you ever use specific stories in your books, or does your research serve more as inspiration?

Research and invention are constantly evolving and interacting as I write. Often, interviews and the stories told to me become so much a part of my imagination that I lose track of where the “facts” end and where my own interpretations begin. In response to some inspiring encounter, I attempt to climb inside the skin of that person, to see the world through his or her eyes, and to dream my way into his or her psyche. At the heart of my work, I have a tendency to write what could be called emotional autobiography. The material isn’t exactly based on my own life, but my inner landscape is a deep reservoir that is fed by the stories of others as well as by my imaginings.

As the daughter of Jewish Holocaust survivors, did you find it difficult to write from Danzig’s point of view?

Without a doubt it was challenging for me to develop the character of Danzig, but my compassion for him—so necessary to the writing process—increased the more I wrote. It was even more daunting to write from his sister Margot’s viewpoint. I went through a very mysterious process of imagining her, then putting those drafted pages away because I felt overwhelmed by a terrible discomfort. For an entire year, I even forgot I’d written them! When I re-discovered the scenes I’d composed for her, they were almost exactly finished, serving as the pivotal chapters that the book needed. I can’t imagine the book without her now.

Throughout the book, Danzig continually uses the phrase “begin again.” Why did you choose to use this particular phrase as his “motto”?

In a way, that motto is mine as much as Danzig’s. I realized during an early stage of struggling with this novel that every artist has to keep facing the empty space, whether it’s a white canvas or a blank page, whether we are listening for music or watching a sculpture take shape in our hands. Each new piece of work means we have to overcome our fears and doubts and find the way to start over, again and again. I am also aware that sometimes I can teach others what I think I know, until finally I really listen to what I’m saying as instruction for myself.

Furthermore, with Danzig in particular, there is some profound historical wound he needs to heal inside himself in order to feel capable of being his own person. That kind of new beginning can be elusive for a very long time.

Why did you choose art as a way to connect your two main characters? Do you paint? Do you model?

For a long time, I wanted to be a painter, but couldn’t quite locate a sense of what I would call talent. Although I did spend some time painting while working on the novel, it was mostly to remind myself what it felt like to hold brushes and focus my mind on a visual language. I love how different painting is from working with words. As for modeling, I have done that kind of work off and on, mostly a very long time ago (when I was in college). I wrote an essay about the experience when I reflected back on it from a great distance, and was able to appreciate how much it taught me about my relationship to my body. (can we give a link here to that essay? it’s on my website)

In using art as a means of connecting Danzig and Merav, I want to show that making peace is an actively creative process, and indeed a collaborative one as well. These two people have to use their imaginations and empathies to reach across the historical and personal divides that could so easily keep them separated. Each pair of potential enemies has the same creative capacity, or so I believe. Not that it’s easy. But in my opinion, this willingness to break new ground, to take a leap of faith in each other, this is what our future depends upon.

Blue Nude ends in an uplifting, hopeful way for two characters who have been through so much pain. Was ending the novel this way important to you?

See above! Even as I find the entire notion of a “happy ending” to be quite complicated, I do want to invite readers to feel that there is hope even in the darkest moments of this story, including the final scenes. Not just to offer a simplistic recipe for optimism, but to explore the fragility and nuance involved in healing the wounds of history, one person at a time. I believe that small movements in the direction of compassion can make a huge difference in the larger scale of humanity.

Your first novel, The Speed of Light, came out in 2001. How was the experience of writing your second novel different?

There are so many ways to answer this question. One obvious concern was how to resist repeating myself, or following a path that felt safe and familiar. I had to be deliberate about making different choices in voice, subject, imagery—and yet I also had to be able to trust that certain themes continued to haunt and interest me, especially the way the past is palpable inside the present.

I think many authors find that after they’ve discovered an audience of whatever size, they suddenly feel as though there are readers with expectations and preferences. That kind of pressure—even if it’s imaginary!—can easily interfere with one’s authentic process. I kept having to remind myself that Blue Nude was an individual piece of work, and that it would find its own place in the world.

Last but not least, I was writing my first novel mainly during summers because I taught full-time at a community college. While writing Blue Nude, I was able to work with far fewer interruptions because I was no longer teaching.

What books and authors have most influenced your writing?

It would take a long time for me to make a complete list, but first and foremost is Virginia Woolf, especially To the Lighthouse and Mrs. Dalloway. Other significant influences include Michael Ondaatje, Anne Michaels, Marilyn Robinson, Michael Cunningham, Don DeLillo, John Banville, and Sharon Olds.

You are an award-winning poet, and your prose has a lyrical, near-poetic feel to it. More than once, readers and reviewers have commented on the poeticism of your words. Do you write this way intentionally, or is it a natural inclination?

Some combination of the two, I think. My inner voices always sound lyrical to me, and I try my best to translate that quality onto the page. My poetry is quite prosaic and my prose is poetic, so I suppose you could say that I’m hovering in the spaces between the two forms. Honestly, I’m not convinced they are so distinct, at least in my writing life.

What project are you working on now?

I’m working on a novel that is set in my hometown of Schenectady, NY. It’s called Electric City. Too soon to say much more than that!

If you could offer one piece of advice to authors writing fiction, what would it be?

My single piece of advice is to persevere. That may sound simplistic or obvious, but in my experience, it’s the hardest and most essential part of the process. Not to give up when it feels impossible to go forward, not to be discouraged by rejections and disappointments of all kinds, not to allow the opinions of others to overwhelm your vision and purpose. The corrollary is not to try to write like anyone else, and not to obsess about the outcome after the work is done. There is something that only you can create. If you devote yourself fully to writing in the most honest way you can, that process itself will be your best reward.